What is PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental condition that develops in response to a traumatic event. It is characterised by intrusive recollections – ‘flashbacks’ – of the traumatising event that cause extreme emotional distress. The condition is associated with a vicious kaleidoscope of secondary symptoms, including depression, anxiety, anger and drug or alcohol abuse.

The term PTSD was first developed in response to the high incidence of trauma in returning Vietnam war veterans to America.

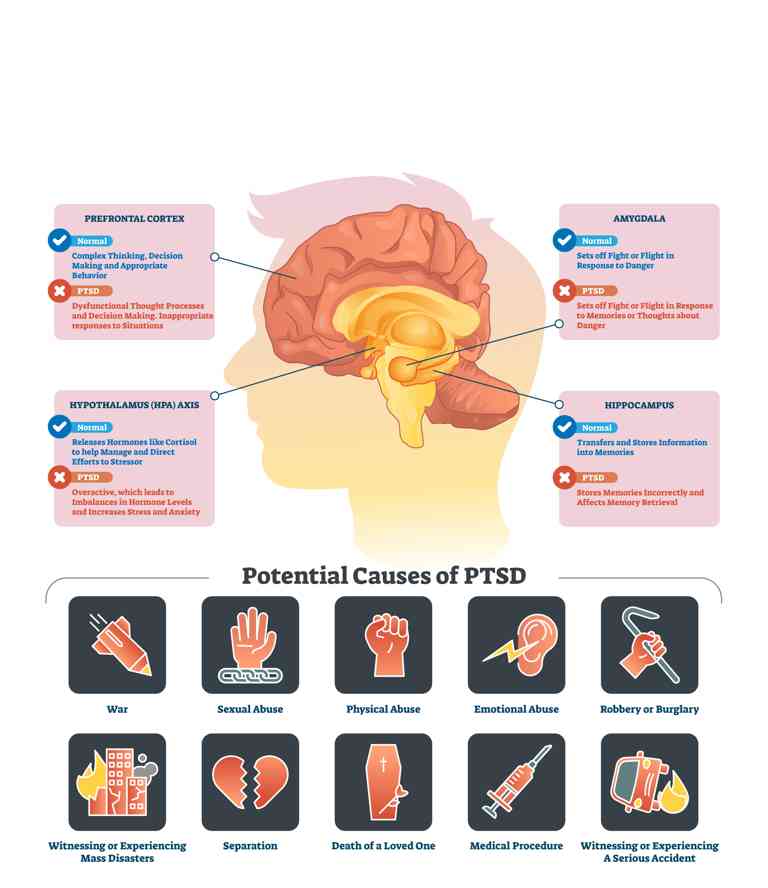

Our understanding of what can be considered ‘trauma’ has grown as the clinical treatment of PTSD has progressed. Traumatic events can include – but are not limited to – assault, sexual violence, warfare, traffic collisions, near-death experiences, natural disasters and the witnessing of violence. But creating hard-and-fast definitions of ‘trauma’ is not necessarily helpful, because we know that trauma can be highly individual, caused by all kinds of different experiences, and can affect different people in different ways.

How does PTSD work?

PTSD develops when a person’s fear response is triggered, particularly when the body has no feasible outlet for the expression of that fear. Experiences of being trapped or paralysed with fear are especially conducive to triggering PTSD.

In trauma survivors, the part of the brain that generates a fear response can remain active long after the traumatising event has ended, leaving them consistently on the edge and secreting stress hormones in low-stress environments. This damages the brain’s capacity to function normally, suppressing the production of serotonin and dopamine, hormones necessary for attention, happiness and energy.

Often, during a traumatic event, the brain also suppresses a person’s senses and physical responses. The essential connection between brain and body is temporarily cut in order to protect the mind. Traumatised people can, therefore, have trouble feeling at home in their own bodies and are especially sensitive to touch.

Common symptoms that people with PTSD experience include:

- Dissociation – feeling like you’re in a haze, like time is slowing down or you are not connected to reality

- Memory blackouts

- Disproportionate angry outbursts and verbal aggression

- Physical aggression and

- Problems concentrating

- Profuse sweating and a heightened sense of feeling threatened

Flashbacks in PTSD

Flashbacks of the original event are induced when a traumatised person encounters a ‘trigger’, a reminiscent sound, smell, sight or sensation. They are extremely frightening experiences. Studies of brain activity demonstrate that flashbacks are experienced as though the event were happening in real-time; a flashback is not a memory, but a re-experiencing of a traumatising event, with the same impact as the first time. This is why traditional talking therapies alone can be ineffective in treating PTSD.

Since flashbacks trigger the same psychological fear response as the traumatising event itself, a person’s behaviour during a flashback can seem, to an outsider, disproportionately fearful or violent. This is why compassion and understanding are essential when working with a PTSD sufferer.

PTSD also suppresses the brain’s capacity for empathy – understanding the emotions and motivations of others. This means that trauma survivors can find it harder to relate to others and can perceive danger in the most innocent of situations. But the formation of strong emotional bonds is one of the most important steps in healing trauma.

How can PTSD be treated?

If you are suffering from PTSD, there is reason to hope. Though debilitating, the condition can be successfully treated using a range of innovative techniques.

Since PTSD can damage a person’s connection to their body, and since sensory experiences can be powerful triggers for flashbacks, the most effective treatments for PTSD combine treating the psychological problems and the physical body in tandem. Acclimatising a survivor to touch, movement and physical expression can help them to overcome PTSD.

Common methods for the treatment of PTSD include:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy, developing personal coping strategies with your therapist that seek to divert negative thought patterns.

- Cognitive Processing Therapy, combining elements of CBT with techniques to help modify, challenge and process unhelpful beliefs following trauma.

- Mindfulness, the purposeful focus of one’s attention on the present moment.

- Dialectical behavioural therapy, the coupling of traditional CBT methods for emotional regulation with ideas of distress tolerance – the acceptance of distressing experiences – and mindfulness.

- Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, involving recall of a distressing image or event while engaging in a simple physical behaviour such as side-to-side eye movements or hand tapping. The processing of the event while engaging in simple, repetitive physical activity can help to desensitise, and can reduce the severity of flashbacks.

More alternative but anecdotally effective therapies include:

- Neurolinguistic programming therapy, a treatment that involves correcting the language that leads to negative thinking, helping the person to divert destructive thought patterns.

- Hypnotherapy, the inducement of a trance-like state in which a person can be gently re-exposed to their experiences in a therapeutic manner.

And more sensory therapies include:

- Sand therapy, in which a person reconstructs their experiences or mental state using toys and sand, creating a safe distance between a person and their trauma from which they can interrogate it in a less distressing way.

- Yoga, tai chi and massage therapy, and other physical therapies that combine bodily experience (stretching, moving or being touched) with meditative contemplation, realigning a person’s mind with their body for healthier processing.

Amalyah Hart

Amalyah Hart is a freelance journalist and content writer, specialising in science communication. She has a degree in Archaeology and Anthropology from the University of Oxford and has completed a Master of Journalism at the University of Melbourne. She writes on psychology, health and health policy, and the environment. She also works in public policy consulting, specialising in the healthcare sector.

Recommended Reading

Get help now

Appointments currently available

Open 8am to 8pm weekdays and 9am to 5:30pm weekends